Delicate Deltas - Fascinating Features of Rivers

- Tom McAndrew

- Sep 30, 2025

- 6 min read

Rivers are among the most dynamic and transformative forces shaping our landscapes. From mountain headwaters to coastal plains, they carve valleys, transport vast loads of sediment, and eventually release this material at the sea. At the meeting point between river and ocean, one of the most remarkable landforms emerges: the delta. These sprawling, fan-shaped areas of deposition are not only geographical spectacles but also cradles of human civilisation, rich ecosystems, and evidence of the delicate balance between fluvial and marine processes.

What is a Delta?

The word 'delta' itself comes from the Greek letter Δ, as the triangular shape of the Nile Delta reminded early scholars of the letter’s form. In essence, a delta forms where a river meets a standing body of water such as a sea, ocean, or large lake, and deposits the load it has carried across its course. Unlike an estuary, which is dominated by tidal processes and often has a funnel-shaped mouth, a delta develops when deposition outweighs erosion, and when sediment supplied by the river is sufficient to accumulate and build outward into the water.

But deltas are far from simple. They are the outcome of competing processes: the energy of the river pushing forwards, the sediment settling as velocity declines, the tide reworking deposits, and the waves redistributing material along the coast. The relative dominance of these processes explains why deltas vary so much in shape and structure across the globe.

The Mechanics of Delta Formation

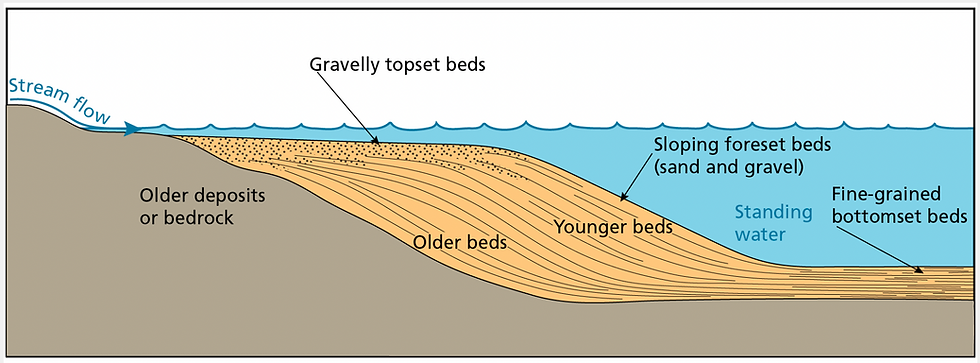

A river carries sediment through processes of erosion and transport, with load ranging from fine silts and clays to sands and gravels. As the river approaches its mouth, the velocity of flow decreases rapidly. Water spreads out, friction increases, and the carrying capacity diminishes. Heavier materials such as sands are dropped first, followed by silts and then clays, which may remain suspended and drift further into the marine environment before settling.

Over time, deposition builds up at the river mouth, obstructing the channel and causing the river to split into distributaries. These branching channels spread sediment across a widening area, creating the familiar fan-like form of a delta. The sequence of sediment deposition is known as a “graded sequence,” with coarser material at the delta front and finer deposits further offshore.

Another important process is compaction. As layers of sediment accumulate, the weight compresses underlying material, influencing subsidence rates and the shape of the delta. Biological activity also plays a role: vegetation stabilises sediments, while mangroves or marsh grasses can trap finer particles. In tropical and subtropical regions, the interplay between vegetation and sedimentation is particularly evident in the creation of highly fertile deltaic soils.

Types of Deltas

Not all deltas look alike. Their shapes tell the story of the balance between river energy, wave action, and tidal influence. Geographers often classify deltas into types based on their dominant process, although in reality most deltas reflect a combination of forces.

The Arcuate Delta

Perhaps the most iconic form, the arcuate delta resembles a rounded, fan-like shape. Its name comes from the Latin “arcus,” meaning bow or curve. The Nile Delta in Egypt is a classic example, fanning out into the Mediterranean with a smooth seaward edge. In an arcuate delta, the river delivers abundant sediment, but strong wave action redistributes it evenly along the coastline. This produces a relatively regular shoreline with numerous distributaries cutting through. Fertile soils and easy access to waterways have made arcuate deltas hotspots of human settlement for millennia.

The Bird’s Foot Delta

Where river energy is strong and marine processes are relatively weak, a bird’s foot delta forms. The Mississippi Delta in the United States is the textbook case, with long, finger-like distributaries extending far into the Gulf of Mexico. This shape results from the river pushing sediment into the sea faster than waves or tides can redistribute it. The distributaries resemble the outspread toes of a bird’s foot, separated by marshes, bays, and wetlands. Bird’s foot deltas are highly dynamic, with channels frequently shifting as new deposits block old routes and force the river to cut new ones.

The Cuspate Delta

Where waves dominate, the coastline may develop a cuspate, or pointed, delta. These tend to form in areas where sediment supply is moderate, and wave action is strong enough to shape a sharp, tooth-like projection into the sea. An example is the Tiber Delta in Italy. Here, the balance is tipped towards coastal processes rather than fluvial energy, giving the delta a more triangular and pointed outline.

The Estuarine Delta

Sometimes rivers enter drowned valleys, or rias, where tides and currents dominate deposition. These are called estuarine deltas. Unlike classic protruding deltas, estuarine types often infill existing bays or estuaries, gradually transforming them into complex wetland systems. The Seine estuary in France demonstrates this type. Such deltas remind us that the line between 'estuary' and 'delta' is blurred and that transitional environments often share characteristics of both.

The Inland Delta

Not all deltas meet the sea. In some cases, rivers deposit sediment inland, creating what are termed 'inland deltas.' These form where rivers encounter areas of very low gradient, swamps, or interior basins. The Niger Inland Delta in Mali is an extraordinary example: here, distributaries spread across a vast floodplain, creating a mosaic of channels, marshes, and seasonal lakes. These inland deltas are crucial ecological zones, providing habitat for wildlife and resources for human livelihoods in otherwise dry regions.

Factors Influencing Delta Development

The shape, size, and sustainability of deltas depend on several interrelated factors.

Sediment supply is crucial. Large rivers such as the Ganges–Brahmaputra, Amazon, and Yangtze carry immense loads from their mountainous catchments, enabling them to build vast deltas. Smaller rivers, by contrast, may struggle to form deltas at all, especially where strong waves disperse material quickly.

The gradient of the coastline also matters. Shallow offshore areas encourage sediment to accumulate, while steep drop-offs make it harder for material to settle. For this reason, the world’s largest deltas often occur on continental shelves with gentle slopes.

Tidal range and wave climate play significant roles. Where tides are strong, sediments may be redistributed into elongated sandbars and mudflats, reducing the prominence of deltaic protrusions. Wave-dominated coasts tend to smooth out irregularities, producing arcuate or cuspate deltas.

Finally, human activity has become a major factor. Dams trap sediment upstream, reducing supply to deltas. Land reclamation, channelisation, and drainage alter natural deposition processes. Rising sea levels and subsidence exacerbate erosion, threatening deltaic environments worldwide. The Mekong and Nile deltas, for example, are experiencing rapid retreat, raising urgent questions about the future of millions of people who depend on them.

Life on the Delta: A Cradle of Civilisation

Beyond their geomorphological fascination, deltas are places of immense human importance. The fertility of alluvial soils, enriched by regular flooding and silt deposition, has supported agriculture for thousands of years. The Nile Delta sustained ancient Egyptian civilisation, while the Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta underpins the food supply of modern Bangladesh.

Deltas also provide abundant resources: fisheries, freshwater, fertile farmland, and access to transport routes. However, their very attractiveness makes them densely populated and vulnerable. The combination of natural hazards, such as flooding and cyclones, with human pressures like urbanisation and pollution, creates fragile environments where sustainability is a pressing concern.

Deltas in a Changing World

Today, the future of deltas hangs in the balance. Climate change, sea-level rise, and altered sediment flows from damming and land use are reshaping these landscapes at alarming rates. The Mississippi Delta has been losing wetlands at a pace measured in football fields per hour due to subsidence, erosion, and reduced sediment input. In the Nile Delta, the construction of the Aswan High Dam drastically reduced sediment reaching the Mediterranean, leading to coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion into farmland.

Conversely, some deltas are growing. The Yellow River in China has historically shifted course many times, rapidly building new deltaic lobes as sediment-rich waters found new routes to the sea. But even here, intensive management has altered natural dynamics.

Deltas represent both the beauty and vulnerability of Earth’s systems. They remind us that landforms are not fixed but constantly evolving under the push and pull of natural and human forces.

River deltas are far more than just pretty shapes at the end of rivers. They are complex, living landforms, born of the interaction between rivers, seas, tides, and sediment. From the bird’s foot of the Mississippi to the arc of the Nile, from the inland floodplains of Mali to the cuspate points of Italy, deltas demonstrate the variety of outcomes when nature’s processes collide.

Sources

Bridge, J. S. (2003). Rivers and Floodplains: Forms, Processes, and Sedimentary Record. Blackwell.

Nicholls, R. J., & Cazenave, A. (2010). Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science, 328(5985), 1517–1520.

Orme, A. R. (1990). The Nile Delta. In R. Said (Ed.), The Geology of Egypt. Balkema.

Reading, H. G. (1996). Sedimentary Environments: Processes, Facies and Stratigraphy. Blackwell.

Syvitski, J. P. M., & Saito, Y. (2007). Morphodynamics of deltas under the influence of humans. Global and Planetary Change, 57(3–4), 261–282.

Wright, L. D. (1977). Sediment transport and deposition at river mouths: A synthesis. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 88(6), 857–868.

Comments